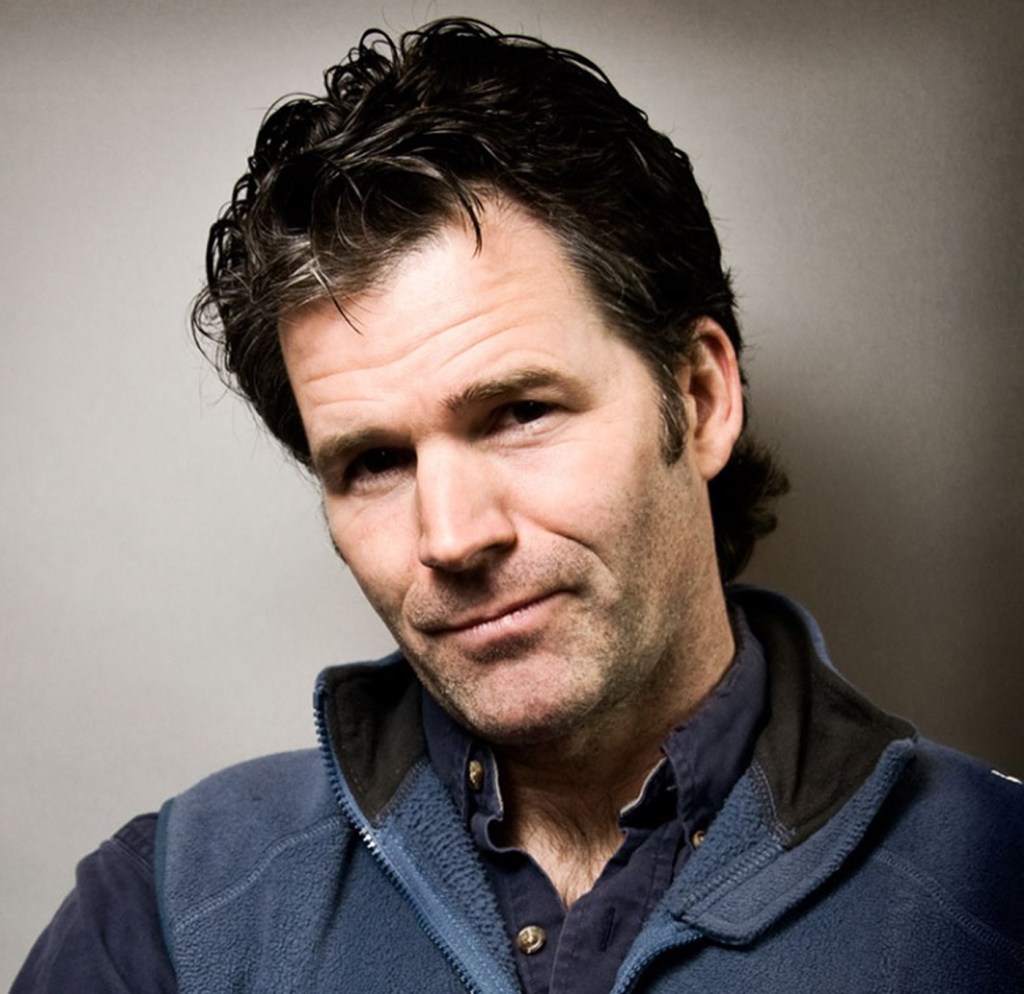

Ghost Dogs: On Killers and Kin by Andre Dubus III (W.W. Norton)

A life-changing event for Andre Dubus III was the 1999 publication of his third book, House of Sand and Fog, which was a number one New York Times bestseller, a National Book Award finalist, an Oprah Book Club pick and a successful movie. Also, for those who read it, a first-rate tragedy.

You won’t be taken onto the set of the film, which starred Ben Kingsley and Jennifer Connelly, or even learn the title of the book here. What you will learn about, from several different angles, is the money it brought in, and how it transformed a life that was heretofore lived at the margins. In interlocking essays, separately published and sometimes repeating information, we hear different perspectives on the great preoccupations of Dubus’ life: violence, family, poverty, and the redemptive power of making things with your hands.

Dubus is the son of the acclaimed short-story writer Andre Dubus, but his father and mother separated early. Dubus’ single mother moved her children dozens of times from one hardscrabble New England mill town to another as she struggled to find meaningful work. The kids were often hungry and cold. Dubus was bullied until he bulked up and fought back, a story vividly told in his memoir Townie. Ghost Dogs is a different kind of memoir, told in overlapping stories—all brilliantly written. He’s one of our finest prose stylists, especially good at capturing working-class (and working) lives. His fiction is embedded in work sites, cheap apartments, diners. The author’s latest novel, Such Kindness, is a hugely compelling example, a tragedy set mostly in a low-rent motor court.

Dubus isn’t much different writing about himself, though the essays here do tend to circle back over some central incidents. From years spent huddled with his siblings in cold apartments watching endless TV, he and his brother were suddenly thrust into the light and vivid life of his mother’s parents’ rustic camp home in Louisiana. “Pappy” is about his grandfather, a pipefitter/craftsman who is never still. He puts these soft New Englander kids to work. Dubus doesn’t spare himself, the person he was at different points in his life. He’s particularly good on violence, especially his own. “Relapse,” the final essay, is about the grown family man who used the House of Sand and Fog money to build (with his brother) a safe home away from urban dangers. He’s been pacifistic for decades, and yet the call of the wild is always there. He recounts two incidents, chance encounters that could have erupt into physical confrontations.

In 2001, having just won a Guggenheim, Dubus and friends are leaving an upscale restaurant where they’ve been celebrating when a young man leaning against a pickup truck yells out a sexual taunt. In an instant, Dubus is in his face and saying, “Watch your fucking mouth.” He recounts, “What you should know, what I’m not proud of writing now, is that I wanted to drop this man.” It’s all tangled up in ideas of American masculinity, virtually the whole theme of Townie. When Dubus does deck a man in a bar who makes fun of his shirt, decades of a softer life are instantly gone and he’s feral once again: “It is as if my last fight was not nearly 30 years ago but just an hour earlier, like I’ve never stopped fighting at all, like it’s something I still do all the time,” Dubus writes. Pride and regret mix when he describes events like this, to his peers and to his children. And when those kids are themselves getting into fights, what’s the right thing to say?

Perhaps the finest essay here is “If I Owned a Gun,” which recounts every encounter—many of them sordid, a couple of them near-misses—he’s had with firearms, and his determination not to have one in the aforementioned family sanctuary. He knows that people who own handguns are 400 times more likely to be victims of them than people who don’t, and—from experience—that “its not loaded” often constitutes someone’s last words. “Yet part of me, inexplicably, still loves guns,” he writes. The weight, the gleam of their polished stocks, the smell of gun oil, all part of another uniquely American rite of passage.

And then there’s the work of the hands. Dubus’s father was never seen to hold a tool of any kind (except, perhaps, his large gun collection) but Dubus became a carpenter and a construction worker—who, until House of Sand and Fog at least—wrote after those jobs were done. He never sits down at a table in this book without mentioning that he built it himself, as well as the loft bed in one of those hardscrabble apartments. He’s definitely house-proud about his refuge in the woods.

Some readers might find this annoying but he writes so damned honestly about all of it. You don’t have to read all these essays, because they do get a bit repetitive, but don’t miss “Relapse” and “If I Owned a Gun.” And, come to think of it, the one about the ghost dogs of the title is also full of revelatory admissions from this self-revealing man. Most people, having kicked their poor pooch, would keep it to themselves. And, finally, if you want to know what it’s like to suddenly come into money, “High Life” is the answer. The stories of big working-class lottery winners going on insane spending sprees are legion, and Dubus lets us know that near-winners of the National Book Award—especially if they grew up poor—are not immune from similar impulses.