Every Man for Himself and God Against All by Werner Herzog (Penguin Press)

By Jim Motavalli

If even half of Werner Herzog’s memoir is true, we’re lucky he made it to his current 81. He describes miraculous survivals all over the world—shooting untamed rapids, a bow-and-arrow attack from an uncontacted tribe, smuggling adventures on the U.S.-Mexican border, close encounters with the wildman actor Klaus Kinski—that are great fun to read, even if their total veracity is in doubt.

Of course, enough of this is well-documented—including the author’s hardscrabble upbringing in postwar Germany, the eating of his own shoes in a bet with filmmaker Les Blank, and the arduous path to completing Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre: The Wrath of God—that the wilder stories seem at least characteristic. Kinski and Herzog were well-matched.

Herzog’s droll, deadpan German-accented voice is familiar from his documentaries. Click on his thoughts vis-à-vis the stupidity of chickens. This book is perhaps best enjoyed in the audio version. The book was written in German and ably translated by Michael Hoffman, though Herzog (who lives in Los Angeles) reads it in English.

Herzog’s films are wildly disparate, but they all grow out of Herzog’s fascination with mankind in extremis, and people who stubbornly refuse to conform to society’s expectations.

Much of the director’s time must be spent trying to get his many films financed, but that material doesn’t make it into the book. The director is (or at least sees himself as) a man of action, and it’s no wonder he became a close friend of the similarly peripatetic Bruce Chatwin (whose novel The Viceroy of Ouidah he made as the film Cobra Verde).

As he tells it, Herzog had zero training as a filmmaker. He just started doing it, directing his first short, Herakles, in 1961. Since then, he’s produced documentaries, features and filmed operas in a steady stream, sometimes two a year. He’s still at it, with the volcanic The Fire Within (2022).

I’ve never seen a bad Herzog film, but I realize from the filmography thoughtfully provided at the end of the book that most of his work is unseen by me. I hope to remedy that, with the help of streaming services.

Herzog the author is very much like Herzog the director—curious, droll, sardonic, funny. He’s a bit of a German fatalist, though hardly a typical German. Like Fassbinder, he’s an internationalist, whose most famous films are set in France (Cave of Forgotten Dreams), Alaska (Grizzly Man), Australia (Where Green Ants Dream) and South America (Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, Ten Thousand Years Older).

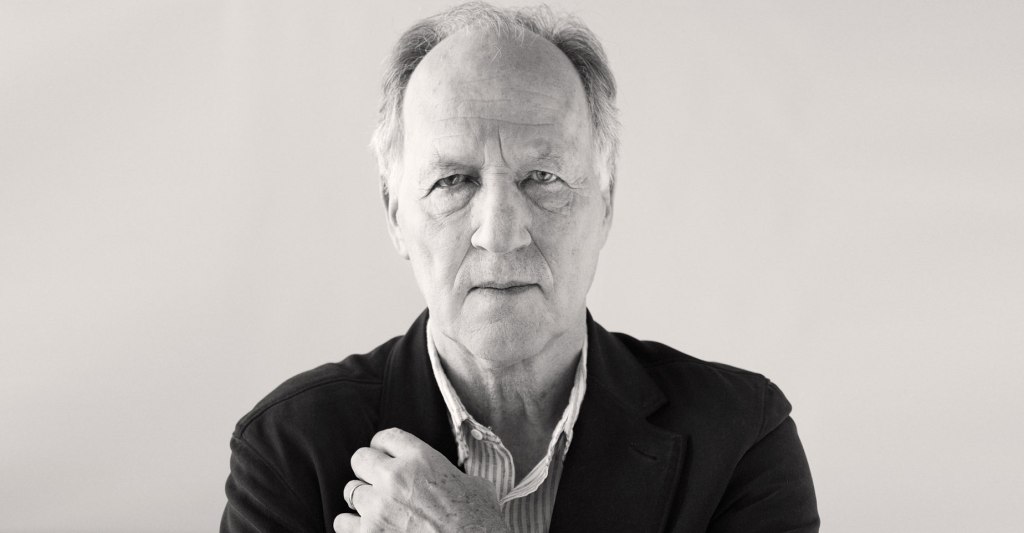

Most autobiographies feature younger, idealized cover photographs of their author. Herzog chooses to portray himself as he really is now, grizzled like his grizzly man, uncombed, and appearing to be in the midst of confronting something distasteful.